I'll never forget the day he blew up the van. I cried many tears that day. The rain from the day held down the smoke of the fire into the evening. You can still drive down our street and see the burn marks on the road. If you click on the article they have pictures of the street and Melida at their house a couple of weeks ago. The pictures I've put on here are the ones I have of Carlos and Alex.

May peace be inside all of us - for Carlos and Alex and all the fallen soldiers

Cindy

Carlos Arredondo did the unthinkable with gasoline, a Marine van, and a propane torch. Two years later, he still burns.

Two summers ago in Hollywood, helicopter cameras broadcast a snapshot of hell: a van in flames, vomiting smoke into the sky like a burning oil well as paramedics nearby loaded a man into an ambulance. Naked but for his shorts, he was strapped to a stretcher, immobilized except for his arms — they shivered, making the man look like a lunatic mime with an invisible squeezebox. That image was carried around the world, and it's why people in California, in Massachusetts, in Japan, in Costa Rica all remember the man who burned himself in Hollywood, Florida, even if they don't remember that the man was named Carlos Arredondo.

Print and broadcast media were all over him for a time — the attention helped pump his wife's cell phone bill to around $5,000 in the aftermath of the accident — but after Arredondo left South Florida to receive treatment in Boston, he practically disappeared from local media. He blew town without ever really answering the question of why a man, even one stricken with grief, would do what he did — namely, damn near kill himself in a government van with five gallons of gasoline and a propane torch.

When a New Times reporter sought an answer to that question of why, part of the answer became apparent as Arredondo drove around the Boston suburb of Roslindale speaking about his son Alex. "The day he born, you know, like any other baby, he cry," says Carlos, a Costa Rican national whose English syntax often follows its own rules. "But it was laughing since then. There's no picture where he's not laughing." Five-foot-eleven and athletic, Alex talked about becoming an electrician until, at 17, he enlisted in the Marines, a move he barely discussed with his worried father.

"My son approached me and said, 'Dad, I'm a U.S. Marine. '" Carlos was stunned. "I said: 'Listen, son, I love you very much, I will support you, but you be very careful, because I don't want you to come back in a body bag.' He said, 'Dad, that's not going to happen. '"

Even as the young man shipped off to Iraq in 2003, he managed to find ways of delighting his family. Early in the war, Carlos and his second wife, Melida, pulled their truck to the side of the road in astonishment when they heard him interviewed from an Iraqi tobacco factory on public radio; he lay in wait for his mother and grandmother to astound them on a visit home in 2004; he summoned his mother, Victoria Foley, to a military annex in Maine during a brief stopover there.

Carlos could have used a good surprise on August 25, 2004, a hot day in a trying summer. His semi-estranged father, an absentee alcoholic who had been suffering liver problems, had died a couple of months earlier, his body found on a roadside in Costa Rica. For the second time in ten years, he and Melida had moved from Boston to Hollywood to be near her elderly mother and had maintained a home on Tyler Street, two miles west of I-95.

The stress of Alex's being gone for almost two years, with so little contact and so much carnage, was rubbing Carlos' heart raw. At the time, the 17-month-old war still seemed to be happening at a great distance, five months after four contractors were maimed and burned in Fallujah and shortly after news broke of prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib. Flag-shrouded coffins were being brought home under cover of night and photographic blackout, as though grief ignored was grief contained. American forces seemed to be fighting bad news abroad so we wouldn't have to face it here, but Carlos clung to every bit of news from the war, good and bad. "I would talk to the ladies in my office," Melida says today. "They'd ask, 'How are you doing?' I'd be honest. I'd say, 'God forbid something happens to Alex. Carlos will just go off the deep end. He could end up hurting himself or other people or trying to kill himself. '"

But on that day — Carlos' 44th birthday — the father was sure he would hear from his son. So it was that Carlos was painting the white picket fence in the yard with a phone in his pocket, hoping for a call, when the green Chevy van arrived full of Marines.

Carlos' first thought was that Alex had topped himself: He had come to visit!

The van stopped, and three uniformed Marines from the Hialeah base came onto the lawn. Marine Sgt. Timothy Shipman, Gunnery Sgt. Syril Melvin, and Staff Sgt. Abraham Negron told him there in front of the house that they regretted to inform him that his first-born son, Alex, had been killed in Iraq.

Carlos was staggered. He ran to look for his mother, Luz Dedondo, the only other person at home. He tried calling a friend in Boston; she didn't pick up. Then he called Alex's mother in Maine and reached Carlos' only other son, the younger Brian. A van was in Bangor too. The Marines there didn't tell Brian; he knew when he saw them that Alex had died. "I said, 'Oh, my God, how ignorant I was,'" Carlos says. He called Melida and over a terrible connection implored her to come home from work.

By then, he was begging the Marines to leave, to end this nightmare, but they weren't going to leave him in such a state until his wife arrived. He went into his garage and brought out a five-pound hammer, walked toward the van and... threw the hammer to the ground. He ran to the backyard and dialed his son's recruiter, only to hear a voice on the other end say that the number had been changed. Nothing was making sense. Carlos went back into the garage.

The Marines later told police that they felt safest in the open, watching Carlos as they waited for Melida. Their decision was one of many things that might have gone differently that day. One of Carlos' friends might have soothed him on the phone. A chaplain might have come with the Marines. The Marines might have come at a time other than 1:45 on an afternoon that reached 90 degrees with 90 percent humidity. They might have restrained the hysterical father or taken him inside.

Another possibility: Carlos might have been out of gas. Instead, he emerged from the garage with a red, five-gallon plastic container of the stuff, something he kept around to fuel the boiler on his pressure washer. He also brought out a propane torch. The Marines called 911. Again, he asked them to leave. They didn't, and to this day, Carlos wishes that they had or that they had knocked him on his ass, because, as he remembers it, the next thing he did was grab the hammer and smash out a window, slicing his wrist on the glass. His elderly mother came to take the gas away from him, but he took it back. Her mouth was moving, the Marines were pleading with him, but he was deaf. He opened the unlocked van door, put the gasoline in, found the hammer inside, and trashed the interior — the dash, a computer, a typewriter, all smashed. He threw pieces out and flung the hammer through the back window.

Now there was only gasoline. He splashed the inside, the seats, the ceiling. Fumes swamped Carlos. He took the propane torch — and as his mother grabbed him to pull him out of the driver's-side door, a spark ignited: "FWWOOO-aaaHHHH," he says, describing the sound. The flames spewed like a wave in the ocean, and suddenly he felt a thousand needles hit him all over. He rolled in the grass in a neighbor's yard, and the Marines helped to extinguish him.

Melida arrived. Paramedics arrived. The media arrived. Carlos' phone, which had fallen from his pocket, rang. Someone handed it to Melida. It was Brian, from Maine. He had been watching the news and wanted to know what was happening to his father.

All Carlos could think when he was looking up at the helicopters overhead was, Oh my God, Oh my God. He cried out that he was sorry and kept asking for Alex. It rained.

Neighbors eventually cleaned up the debris. To this day, the street in front of 5430 Tyler St. bears a scorch mark.

Rain is falling outside, as it has for days in the Boston area, and Carlos has retired to the one-car garage in his two-bedroom house. It contains a collection of tools, no fewer than eight of Carlos' old crutches, a motorcycle that penury may soon compel him to sell, and, most prominently, a trailer bearing a full-sized, flag-draped coffin with a pair of Alex's combat boots lashed to the top. It will be a prop in the next morning's Dorchester Day Parade. "See these pieces of wood?" Carlos says, indicating some planks. "I will make a frame. I will put one over there, one more here, one more here. I got that on wheels. It's very important. I really want to be in this parade tomorrow."

After years of treatment, Carlos at first glance displays almost no signs of his injuries. A jutting jaw and curly black locks give him, at 45 years old, the look of a telenovela star, with a ropy physique built in part by riding bulls as a young man. The burn scars that peek from under his shirt are broad but pale, on par with a mottled suntan. His legs fared worse. The skin on his shins remains a sick shade of purple-brown, covered in spots, as though he had peeled the bark off the trunk of an old tree, as brittle and delicate as his emotions.

In his darker moments, he suffers sudden crying jags. In the console of his truck (which has 20 magnetic troop-support ribbons on its tailgate), he carries a bottle of prescription pills "for anxiety and also, you know, to get not too emotional," he says. Those emotions often keep him from working, though his garage brims with the tools of a handyman, and his barbecue-grill-sized pressure washer stands ready to clean rooftops. On this day, in early June, he hasn't worked in weeks.

But in his better moments, which are often, he exudes a Roberto Benigni-esque joie de vivre, born out of a childhood when his mother struggled just to provide bananas and potatoes. He doesn't share what he sees as an American tendency to whine about not having enough. "You have no idea, pal, you have no idea," he says. "Let me go play some soccer while you are crying."

Joy and opportunity occur to him in simple things. Upon being told one evening that there was virtually nothing in his fridge but bottled water and loaves of bread, he said, "That's all we need. We can make toast — we can do a lot with that." Before bed, he sometimes tells his wife that he's excited to sleep just so he can wake at 5:30 a.m. to drink coffee.

His recovery has been a long one; after he cooked himself alive, all was chaos. Second-degree burns covered 26 percent of his body. When he stirred, he cried that he wanted to see Alex. His mother, alarmed, told hospital personnel, who, thinking he might be suicidal, placed the bleary, dehydrated Carlos in four-point restraints. In the blurry, disposable-camera snapshots that the family took of Carlos in the hospital, he looks like a man rescued from a desert — parched, too dark, cracked — then mummified in white bandages. "The right ear," Melida recalls, "looked like a pork rind." His hospital bill for three hours at Hollywood's Memorial Regional Hospital came to a tidy $10,000. The week he spent at Jackson Memorial in Miami rang up another $42,000. After some drama, the hospitals settled for much less; a deluge of supportive e-mails, calls, and letters may have helped the police department decide likewise not to charge Carlos with any crime. Political timing might not have hurt either, as the Republican Party held its convention in New York City four days later.

He traveled back to Boston for Alex's funeral in heavy bandages and spent the duration under heavy dope. Through the back of an ambulance behind the hearse, he watched his son's funeral procession. Five hundred people, including Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney, signed the guest book that day. Carlos' soccer team arrived, in uniform, and presented Melida with a thousand dollars in an envelope. Carlos remembers it through a morphine fog. Only later, when he saw pictures of his son lying in state, did Carlos remember standing over Alex, his tears falling and smudging the funerary makeup.

He traveled back to Boston for Alex's funeral in heavy bandages and spent the duration under heavy dope. Through the back of an ambulance behind the hearse, he watched his son's funeral procession. Five hundred people, including Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney, signed the guest book that day. Carlos' soccer team arrived, in uniform, and presented Melida with a thousand dollars in an envelope. Carlos remembers it through a morphine fog. Only later, when he saw pictures of his son lying in state, did Carlos remember standing over Alex, his tears falling and smudging the funerary makeup.

Within days, letters began arriving, and they didn't let up for weeks. People from all over the country sent cards, blessings, and cash that they said were to help him heal. One man from New Jersey sent a check for $1,000; when Carlos and Melida called to thank him later, he sent another check for $1,000. A high school classmate of Melida's sent $5,000. Most were in denominations much smaller — $100, $30, as little as $7. A family from California sent $10 with a letter that the two children asked to have their allowance sent to Mr. Carlos Arredondo rather than spend it as they had planned, at McDonald's.

He received the balance of his treatments at a Boston hospital. As soon as he was well enough to travel, Carlos fled to Costa Rica. The din of the media had become too great. When a Japanese news crew found him, he relented to speak with them — after all, they had come so far, going first to Miami before tracking him to Central America.

After Hurricane Wilma romped through South Florida, Carlos was back in Hollywood, repairing his fence with the scraps of fence that others were discarding. Cold weather renews the pain of his burns, so he spent much of the holiday season in his home in Hollywood, much of it in solitude. For New Year's Eve, he got drunk on beer at home alone.

But, at least to hear his wife tell it, that was around the period that he transitioned out of his darkest grief.

Now he finds it easy to talk about that terrible day in Hollywood. "How ignorant I was!" Carlos cries out at one point. "When I saw them, I thought Alex was here. It was a happy moment. It was my birthday. I was being selfish. I wasn't prepared for that.

"Experience with him gave me so moments unbelievable. But this moment was going to be the worst of my ever life. Do you understand? The worst, the worst, worst, worst!"

Alex was the 968th U.S. soldier killed in the war. It took the family nine months to get any details about his death; about a year ago, they received an e-mail from a Marine sergeant explaining that the young lance corporal's battalion had come under fire in Najaf. After a three-hour gunbattle, as Alex prowled through a four-story hotel, a bullet caught his temple. He was 20 years and 20 days old.

Alex was the 968th U.S. soldier killed in the war. It took the family nine months to get any details about his death; about a year ago, they received an e-mail from a Marine sergeant explaining that the young lance corporal's battalion had come under fire in Najaf. After a three-hour gunbattle, as Alex prowled through a four-story hotel, a bullet caught his temple. He was 20 years and 20 days old.

Carlos is reminded of Alex every time another soldier is killed (more than 1,600 have died since). Which is how he came to have a coffin in his garage. In October of last year, the 2,000th soldier of the war died, from injuries he sustained in a bombing. Hearing the name of that dead soldier, George T. Alexander, sent Carlos into despair. He began toting around a box made up to look like a military coffin. Then one day, he met a man in nearby Cambridge who offered him a free coffin from what was apparently a funeral home showroom, complete with flag. On days when it feels necessary, Carlos parks it somewhere visible and offers to passersby a copy of a letter Alex wrote. The father says, "My son wrote this letter on the way to war. It was his first letter home. It would be an honor if you read it."

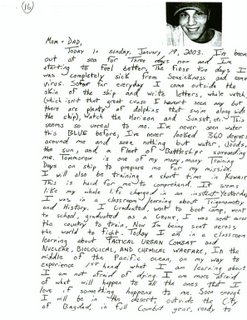

The clear-eyed letter from January 2003 reads, in part: "I am not afraid of dying. I am more afraid of what will happen to all the ones that I love if something happens to me. Soon enough I will be in the desert, outside the City of Bagdad [sic], in full combat gear, ready to carry out my mission, wondering how this all happened so fast..."

Tomorrow's parade will mark the first time he's had the coffin off the trailer. With help, he lifts the casket and turns it crossways on the edge of the trailer, to clear workspace. He saws wood to build a rectangle he will fit with large wheels, to drag the coffin like a wagon. He would like to build it with bolts — which he considers precious enough to collect from the ground, just as he scrounges scrap wood from trash bins — but with only a handful of good bolts, he must resort to inferior drywall screws. With his work days few, he watches every expense. "There is a Home Depot nearby," he says, "but it doesn't do me any good."

In 1963, Carlos went to see John F. Kennedy in San José, when the president was in Costa Rica for a summit, his penultimate international trip. Although he was actually too young to remember the experience, his mother would remind him of the visit. He absorbed the lofty rhetoric of 1960s icons like Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., watched Spanish-language Three Stooges on television, and dreamed of traveling to the United States.

In 1980, at age 20, with just a year of high school under his belt, he talked a truck driver into stowing him and two friends through Nicaragua, then torn by civil war. A few miles from the border, Anastasio Somoza's government soldiers stopped the truck. He and his fellow travelers were held in a mansion serving as a prison until the Sandinistas claimed the place. Eventually, he made it to Long Beach, California, where he worked at a beach restaurant near the Queen Mary, and then to Boston, where his first introduction to the city's racial realities came courtesy of some toughs who chased him out of South Boston when he asked how to get to the John F. Kennedy Library.

At 23, he became a father, and an indulgent one at that. In the backyard of the family home, he would build ridiculous bouncy swings out of the giant springs used in garage door openers. On hot days, he would load the back of a pickup truck with a small pool, fill it with water, plop the boys in, and drive to get ice cream. He drove through the most godforsaken stretch of potholes in town. "You hear the laughing, you hear the screaming, and there they go," he recalls. "They try to hold on. They love it. They got bruises, and they got something to show the other kids. They want to bring other kids to the ride, but I only allow two or three kids onto the ride, because I did not want them to get hurt. 'Can we go to the bumpy road, can we go to the bumpy road?' Why not?"

His divorce from the boys' mother was no smoother. They first separated in 1988, when Alex was about 4, with the divorce becoming final in 1996. Out of impulsiveness and sheer stupidity, Carlos was twice arrested for trying to contact or visit the kids when the court dictated they were to be with their mother. Finally, he said to hell with it, packed his clothes, gave away most of his possessions, and told his landlord he was moving with Melida to South Florida.

Since Alex's death, Carlos has become one of the more visible figures in a culture he never wanted to be a part of. He spent time at Cindy Sheehan's Camp Casey last summer, where the reception was warm except for some hecklers on horseback. ("My dream was always to see American cowboys," Carlos says. "So they made my American dream come true, even if they were yelling at us.") Carlos and Melida have returned to South Florida for Broward Anti-War Coalition gatherings; they plan to spend the weeks before the mid-term elections this year in Broward, speaking and campaigning.

On an antiwar bus tour this spring to Washington, D.C., Carlos met one of the cheerleaders of the Iraq War, former Assistant Secretary of Defense Richard Perle. Perle told him he hoped he would one day be proud of the job Alex and others did in Iraq. Carlos told him he was already proud of Alex and gave Perle a copy of Alex's letter. Perle later sent a personal check for $1,000 to the scholarship fund Carlos established in his son's name. Though grateful, Carlos plans to write him a letter thanking him and telling him where to get off.

"On Memorial Day, I went to visit this family, the Lucey family," Carlos says one afternoon, referring to Jeffrey Lucey, a young Marine from a nearby town. "Kevin and Joyce, they are the parents. He went to Iraq; he was a U.S. Marine. He come back with posttraumatic stress disorder. He was trying to be a normal citizen. Was very hard for him. One of the things that happened there was he shot and killed two Iraqi soldiers. That was the biggest torment that he had. He took orders from someone who said, 'Shoot.'

"He commit suicide by hanging himself in the basement. His father, when he returned from work, he look here and saw his son hanging. He was looking down at the ground, he see his son there, he don't even go in the basement again."

When Carlos makes speeches, he tells people that the war is a mistake, but mostly he talks about Alex. A few days before the parade, he spoke at a house party a few blocks from Harvard University. A rock band called Disaster Strikes invited him to join them on the floor before a show. About a hundred young people listened respectfully as he talked about his experiences. "People here remember that," says the band's singer, who goes by J.R. "They see him and they say, 'That was that guy? Holy shit. '"

Sometimes after these talks, people tell Carlos he is their hero, though as a wartime immolator, he is perhaps best admired without being emulated. At least four Americans burned themselves to death in protest of the Vietnam War; the most famous among them was Norman Morrison, a Quaker who torched himself outside Defense Secretary Robert McNamara's Pentagon office window in 1965. In 1991, a college student named Greg Levey burned himself up in the Amherst, Mass., town square in protest of the first Gulf War. Carlos' burning, unintentional though it was, still carries part of that resonance. A Pulitzer Prize-winning Rocky Mountain News story on the Marines who notify families of casualties mentioned Arredondo's as a worst-case scenario.

"If someone shoves Carlos," Melida says one night, "he'll shove 'em back harder. That's the truth of the matter. And I see it. But I actually think he is a pacifist, because he wouldn't want to be shoved to begin with."

Carlos adds, in his imperfect English: "I didn't born violent. I born happy. Always in happy."

"The way it's been depicted," Melida says another time, "is that Carlos got the news and went off, burned the van. But the whole protocol was questionable. He was told on the front lawn. It's a hot, summer day in Florida; he's painting a fence. He asked them to leave many, many times after they gave him the news. They didn't want to leave, and he got pissed off, on top of being really, really hurt."

"No, not pissed off," Carlos adds gently. "I wasn't pissed off."

"You were frustrated."

"No," he replies. "No, it was a... " Carlos says, and pauses to consider.

"Yeah, it could be frustrated, but all the mixture I was feeling, you know?"

Nearly two years after the accident, that's about as well as he can explain it. Carlos Arredondo remains a volatile guy, and trouble yet stalks him even when he least expects it.

The day of the parade is cool, overcast, and dry, blessings all. The line of dancers, marching bands, and antique cars stretches back ad infinitum, it seems. Somewhere toward the back, lining up on a side street, is Carlos, clad in a houndstooth jacket, a black shirt with a black bow tie, slacks, stout shoes. A bagpipe corps warms up on the corner beside him as chubby-thighed majorettes file past, and nearby, an antique fire truck carries the New Liberty Jazz Band. He and Melida have brought their two rat terriers, who sit in a little high-walled wagon.

He's harried. The posters of Alex he brought can't be carried on sticks — some parade regulation — but a Vietnam vet ex-Marine named Winston offers to help. As Carlos begins to introduce himself, Winston says, "I knew your story before anyone. We have a grapevine."

The Dorchester People for Peace group lines up in front of Carlos with a broad banner; except for Carlos and another man, everyone has at least some gray hairs. Slowly, the line begins to lurch.

"How long is the parade?" Carlos asks the older veteran.

"About four, four-and-a-half miles," he replies.

"Oh," Carlos says, "what about your injuries?"

"I don't have any injuries," Winston says. "Just — up here."

"We all do," Carlos says. He tows the coffin with one hand, and with the other, he holds a double-sided poster with photos of Alex — one with his brother, one of Alex in uniform, and a third of him lying in state.

The head of the parade drags up a hill. The snare drums of a bagpipe corps and the cheering are cacophonous. At the top, a man recognizes Carlos.

"I'm sorry for your loss," the man says. Tears pool in his eyes but do not fall. "I can't imagine."

"This is a letter my son wrote," Carlos says as he pulls an envelope from his jacket pocket. "His first letter on the way to war. I want to share it with you."

"Thank you," the man says. "Thank you for being here."

As Carlos turns the corner onto Dorchester Street, the main drag through the village, the Dixie Land Jazz Band strikes up like a warped New Orleans funeral march following a Scottish dirge, with Carlos between. He trudges with his head down, with the poster of his sons' faces smiling out at the crowd and the image of his boy in the coffin facing back at him. He doesn't see the swath he cuts, but it is stark. Men and women clap, wince, salute, gasp "Oh my God..." One woman in a lawn chair grabs her small daughter and begins crying. Kids who have been wiggling to the jazz stop, tug their parents' sleeves, and point. Once, when the parade stops for some reason or another, a child on the sidewalk drops a small ball, which rolls into the gutter. Carlos leaves the coffin, walks over, and jumps at the ball. He lands with his feet on either side and tosses it straight back to the little boy, soccer-style, then wordlessly walks back to the coffin.

As the city blocks scroll past, the neighborhoods morph from working-class white to black to Hispanic and finally to Vietnamese. Old men in front of Desmond's Pub applaud. Some joker with a cup in his hand calls out, "This is sad, man. Don't bring down the parade." A kid on a minibike rolls up to ask, impishly, "Is somebody really in there?" At an intersection, a large police officer starts clapping, and it spreads through the bystanders.

Then, farther down, from the sidewalk: "WHAT THE FUCK?"

The voice sounds like an ogre's. It belongs to a large man with a gray beard.

"HEY! I'M TALKING TO YOU! WHO THE FUCK DO YOU THINK YOU ARE?"

He's walking out of the crowd, into a gap in the parade. He is behind Carlos but gaining on him.

"WHO DO YOU FUCKING THINK YOU ARE, BRINGING A COFFIN HERE?"

Carlos, silent, hands off the picture of his son, to clear his hands. He has decided he will not let this man touch the casket. The man keeps asking Carlos who he thinks he is, and pointing, and stalking closer. Another marcher steps between them; the angry man rips at a campaign sign in the marcher's arms. "His son was killed!" someone says.

Who the fuck does he think he is? He was a father who was shoved as hard as he could be shoved — now, he's not sure who he is, because for Carlos these days, the parade never stops. He is through the fire, and yet he is not. He carries pills in his truck. He thought his son had come home to visit. When troops are beheaded, he goes to the cemetery to cut the grass, then drives around with his coffin until he runs out of gas. He has a letter his son wrote on the way to war, and he would be honored if you read it. Jeffrey Lucey hanged himself in the basement. Alex was shot in the head. It was Carlos' birthday. It was the worst, the worst in his ever life. He is emotionally incapacitated, and he is as alive as anyone you've ever seen.

The man pushes toward him — and then stops, as reason finally gets the better of him. He stalks back down the block, muttering. Carlos is relieved. "I'm glad he went away," he says. "I would not have let him touch the coffin. I would have grab his shirt, push him onto the ground, held him down until — something."

Carlos' Marine friend explains that he recognizes the man from the neighborhood. "His brother's in Iraq," the veteran says. "I tried to talk him out of going."